The self-defeating drive by countries to impose export controls on medical gear in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic has spread like an infection to foodstuffs. Major cereal exporters like Russia, Kazakhstan, and Vietnam are implementing or flirting with export restrictions that threaten to roil global food markets and—as we learned during the 2007–08 and 2010–11 food price spikes—augur poorly for global hunger and political stability. G20 member states, many of whom are major exporters of staple cereals, must avoid protectionist trade measures and act proactively, through commitments to intervene in forward markets, to ensure food commodity price bubbles do not emerge or are popped as soon as possible.

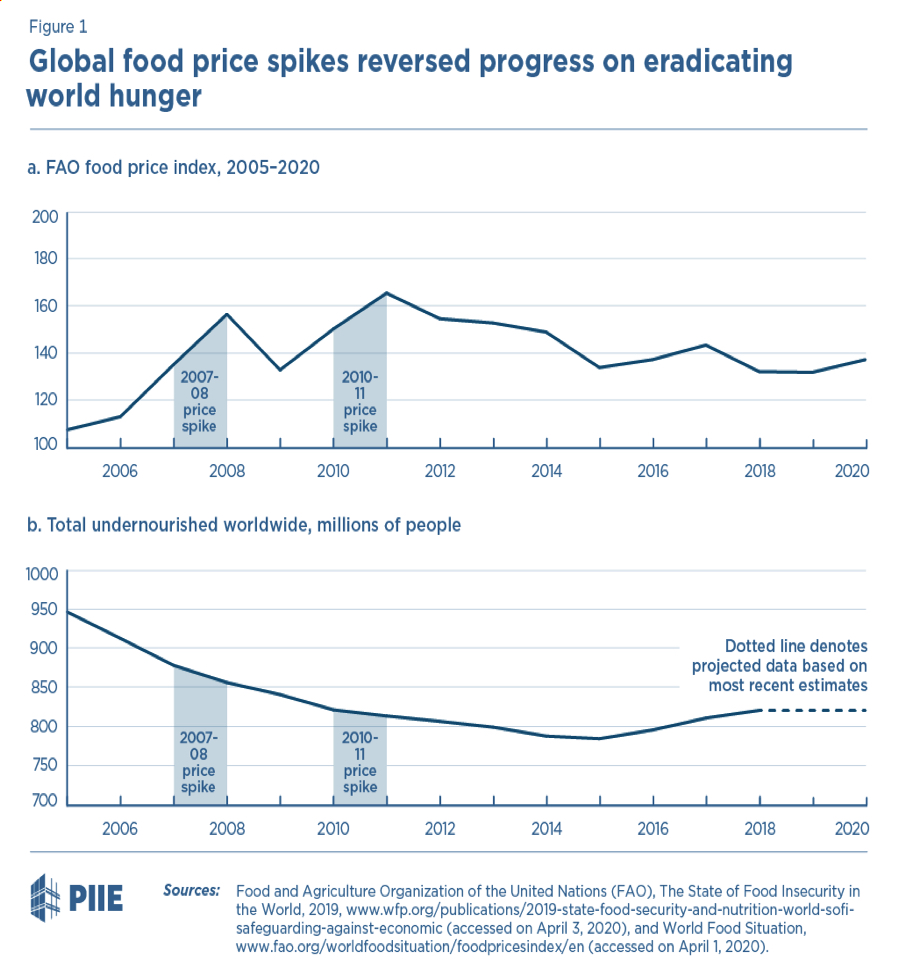

The COVID-19 pandemic is spreading amid troubling increases in world hunger. The slow but consistent progress in eradicating undernourishment has been reversed in the past five years. The current level of 821 million undernourished worldwide, a staggering 10.8 percent of the global population, is the highest since 2011 (Figure 1). Not coincidentally, 2011 was the last time global food prices spiked, driven in part by export bans implemented by G20 members, particularly Russia and India. That price spike considerably slowed the decline in the number of undernourished worldwide. And like an earlier spike in 2007–08 sparked demonstrations and riots in 48 countries, the 2010–11 spike fuelled grievances that motivated the various Arab Spring uprisings.

The increase in hunger that accompanies global food price spikes is bad for human health eo ipso. But it would also make attempts to contain the spread of COVID-19 and effectively treat the disease much more difficult. COVID-19 is particularly unsparing to those with compromised immune systems, and nutrition is obviously key to human health. Several of the most common underlying health conditions in COVID-19 deaths are cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which are both linked to obesity. The effects for undernourished populations are less well known, in part because to date the pandemic has primarily been studied in developed and middle-income countries, where both chronic and acute undernourishment are comparatively (and thankfully) rare. But undernourishment is clearly a cause of immunodeficiency more generally, so a spike in hunger would likely make affected populations much more susceptible to infection and COVID-related mortality.

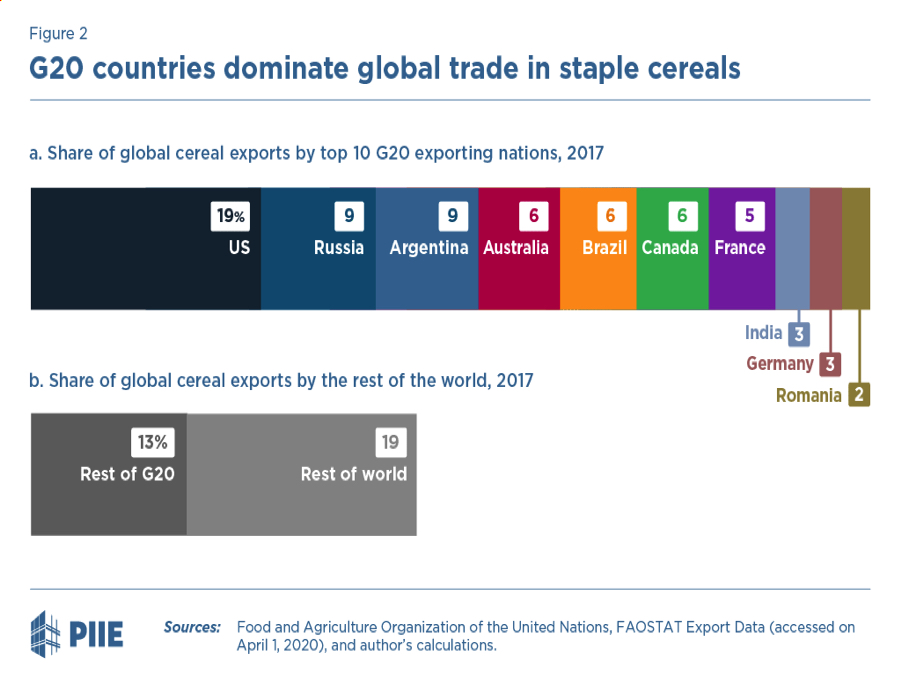

In uncertain times, staple cereals like wheat, maize, and rice (plus more minor and thinly traded “pseudo cereals” like buckwheat and quinoa) are some of the most hoarded types of food: What they may lack in complete nutrition they more than make up for in storability and ease of bulk purchase. They are also widely traded. Global markets for cereals, particularly maize and wheat but increasingly rice, are important for meeting the dietary needs of billions of people worldwide, especially in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. And the G20 is responsible for meeting a huge share of these needs. Collectively, its members accounted for 81 percent of global cereal exports in 2017 and nine of the top ten largest exporters in percentage terms (Figure 2) (the other being Ukraine, which is included in the “Rest of world” category in the figure). Several major G20-member exporters, especially Australia, Argentina, and Canada, export close to or more than half their crop. For some other major G20-member exporters, the exportable surplus is a much smaller share of total production—in India’s case, roughly 5 percent.

These are certainly uncertain times. The COVID-19 pandemic is causing runs on local food markets worldwide, and business and political leaders are urging calm. But several major food-exporting countries are taking matters farther. Russia, the world’s second largest exporter of cereals (Figure 2), was the first mover—and so far the only G20 member—to implement a ban on, in its case, the export of processed grains. Soon after, major non-G20 exporters like Kazakhstan, Thailand, and Cambodia followed suit. Vietnam, the world’s third largest exporter of rice, did not impose an export ban but put a moratorium on new export contracts as it assesses domestic stocks. On March 30, 2020, Cambodia joined the list of countries announcing limits to exports of certain agricultural products, which took effect on April 5. This is a particularly painful decision for a country that has been considerably successful in building a market share in rice.

The logic behind this move to protectionism is simple: As consumers hoard products, demand and thus global prices go up. Fearing shortages due to hoarding, food-exporting countries resort to restricting their exports in order to ensure adequate domestic supplies and shield their consumers from price increases. To some extent, these policies are successful. But they impose a variety of large losses, specifically on domestic producers, who neither get accurate demand signals nor benefit from higher prices in global markets. In the short run, such policies depress farmers’ incomes and export revenues. Over the longer term, they distort incentives for farmers to invest in expanding productive capacity, which is necessary to increase supply and bring down food prices.

Moreover, these restrictions are a crude means of addressing food insecurity. Unlike other mechanisms for preventing food shortages and addressing acute needs, export restrictions operate as a general consumer subsidy, with the welfare benefits accruing disproportionately to comparatively well-off households, rather than just the poor and food-insecure.

Lastly, export restrictions are classic beggar-thy-neighbor policies that throw costs of adjustment back onto international markets and exacerbate the very dynamics they were intended to prevent. Hoarding—at the individual and country levels—is rational if one expects the other to do so. The announced bans signal to markets the intention to hoard, encouraging buyers to panic buy and drive up prices even further. Export restrictions were found to have added as much as 45 percent to world rice prices and 30 percent to wheat prices during the 2007–08 crisis.

After the food price spikes of 2007–08 and 2010–11, which plunged millions into hunger and fueled political instability across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, the G20 committed to relatively minor reforms including not taxing or restricting exports via World Food Programme (WFP) food purchases for humanitarian purposes and attempting to improve transparency in food commodity markets. These were soft commitments at the time, but the current situation calls for much more aggressive, proactive steps to forestall a crisis in the global food system.

A coordinated G20 response would consist of three basic elements:

- The G20 should disavow export restrictions, with a potential exception of India, the lone G20-member major exporter with a large (in both absolute and percentage terms) undernourished population. If this measure proves infeasible, the G20 could move to adopt some best-practice provisions for consultation and policy coordination as embodied in Article 26.2 of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) . While recognizing the rights of governments to enact export restrictions in order to prevent critical shortages, the TPP agreement requires TPP-member exporting countries to notify and consult with TPP-member importing countries beforehand if export bans remain in place for more than 12 months. Prior notification should smooth market responses—thus providing positive spillovers for non-TPP countries in the form of less volatile markets—and allow TPP-importing countries time to seek alternative sources of supply. These consultations could simply be extended more widely with importing countries via the World Trade Organization. This would fall short of the “first best option” of doing away completely with export bans, as already called for by a G20-commissioned report on food price volatility in 2011, but it would be a good next best step.

- The G20 should coordinate around a set of best practices for ensuring adequate domestic supplies through (1) limiting purchases by domestic consumers at retail points of sale, such as supermarkets and grocery stores, (2) reducing taxes on food grains, (3) where possible, tapping into domestic emergency stocks to prevent speculative price bubbles from forming, and (4) using more targeted transfers—like food stamp programs—to address the needs of the most vulnerable populations. These best practices are well known and have been discussed within the G8 and G20 frameworks.

- The G20 should commit publicly to intervene should prices in global markets begin rising rapidly. These interventions could take two principal forms. First, the release of physical stocks—and in some cases, just the announcement of the intention to release—can help calm markets and prevent panic buying. For example, as rice prices spiraled in 2008, G20 member Japan announced it might release stockpiled purchases of US-exported rice. The announcement alone helped bring down prices 14 percent in a single week. Second, G20 member states should commit to implementing virtual grain reserves. Just as central banks often intervene in currency markets to manage exchange rates, G20 member states could commit to intervening in futures markets via progressive short-selling until prices stabilize. While G20 member states have committed to avoiding currency manipulation, this type of coordinated market intervention could be extremely helpful in forestalling price bubbles.

The COVID-19 pandemic threatens global food security. The G20 should take aggressive steps to safeguard against one public health crisis leading to another.

This blog was originally posted at https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/ensuring-global-food-security-time-covid-19 and is reposted here with the permission of the author and the Peterson Institute for International Economics